Calusa Indians

The following extract is from Chapter 5 – Tara. It’s a flashback scene from Tara as a seven year old, the day her father first tells her about the Calusa Indians. Some of the research for the book came from the following links, Florida Museum Of Natural History and a Video Documentary (a short documentary about the Calusa Indians and the mound house at Fort Myers Beach SW Florida.

Note: A huge thanks must go to William H. Marquardt, Ph.D., Curator of South Florida Archaeology and Ethnography, for graciously assisting me by checking my research and excerpts referring to the Calusa. As an author of several books himself, including co-author of The Calusa & Their Legacy, I felt like I’d won the lotto the morning I opened my email to find his response with my critiqued document attached. Thank goodness I followed the lead to contact him because my (cough, splutter) research, left much to be desired. That said, I must say if there are any errors, they are very much my own and/or due to ‘creative’ necessity or the need to engage some poetic license.

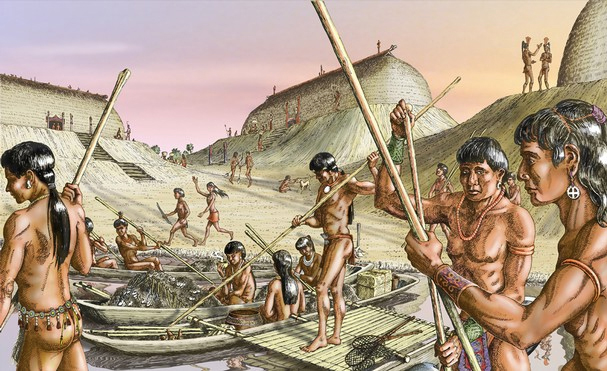

Note: Artists impression of the Calusa Indians from the website Manataka American Indian Council, photo credit to Exploring Florida.

Chapter 5 – Tara

Two weeks after my seventh birthday, a five hundred pound stone bench arrived at our house, marking the beginning of my fascination for indigenous culture, beliefs and music.

Our property had its own private beach overlooking the Gulf Of Mexico. Dad directed the delivery guys to place the bench on top of an ancient Calusa shell mound located at the bottom of the garden. He wanted it to be a sort of monument, something to remind us of our earlier settlers.

Etched into the stone were the words, ‘Calusa – The Shell People’.

Being an artist, Dad felt connected to these fierce and brave warriors. They were an advanced culture known for their creativity in art and music. They built huge shell mounds and engineered complex canal systems to enable them to travel from their villages and ceremonial centers to coastal trading posts. The Calusa sustained thousands of their people with the bounty of an ocean, harvesting much of their food from estuaries teeming with pigfish, mollusks, sea turtles and sharks.

Many of the shell mounds were refuse piles, an archeologist’s dream. These ancient oceanic compost heaps hid a wealth of information and artifacts, revealing the Calusa’s way of life.

Dwelling mounds were built to escape rising sea levels, at least that’s the consensus. For me, the most interesting are the ceremonial mounds, massive semicircular structures, half a mile across with finger like deltaic lobe formations, snaking out from them. Some believe these mounds were ritual gathering places, like Stonehenge, where tribes from many miles around would congregate.

If I hadn’t fallen into singing, I think I may have ended up studying archeology. The thought of bringing history to life, of stepping back in time and literally digging up the past, holds a deep seated fascination for me.

Our mound is fairly small, approximately eight feet high, forty feet long and twenty feet across. It’s mostly buried and overgrown. According to Dad, the original structure was most likely three times the size.

Aunt Ella insists our mound is sacred, possibly a burial mound. She feels things there, but that’s another story.

All Dad feels is respect and admiration. The bench was his way of paying homage to the Calusa. It’s a peaceful place to sit and revel in the beauty of our little piece of paradise while appreciating those who came before us.

“You know, Tara, not much is known about the Calusa and where they came from. It’s even possible they were ancestors of the original Archaic people.” We sat on our stone bench for the first time, warmed by the midday sun, its heat diluted by a cool Gulf breeze. I still remember the heady scent of the ocean, mixed with clay recently stirred by the workmen who set the bench in place earlier that morning. “When I was a young boy, a very wise man, Joseph Black Horse Thorpe, told me the Calusa believed our island was a mystical place, a magical place.”

“Why did they think it was magical, Daddy?”

“Thunderheads.”

“Thunderheads?”

“Joseph told of many legends passed down through generations. He said the Calusa would often witness dark, thunderous storm clouds building up over the Gulf, threatening to move inland. These storms would mysteriously veer off, heading north or south. The Calusa were convinced Marco Island was a sacred paradise. They felt the Island’s soul.”

“What’s a soul?”

“The soul is like your spirit, a place where your emotions live. Let’s see, think about the way you feel when you sing from your heart.”

“Like, when a song sometimes makes me feel like crying?”

“Yes! That’s when your soul speaks to you. You can’t see it, but you can hear and feel it inside the words and melodies.”

A dreamy expression floated across Dad’s face that day, the same look I see whenever I sing for him.

My thirst for knowledge about the Calusa and other tribes continued to grow over the years. I wanted to know more about their way of life, their rituals and ceremonies. Most of all, I wanted to know about their music.

I first met Shada, of the Seminole tribe, in my late teens. She described music as a gift from our creator. She became my teacher and was careful to instill in me the ability to sing with reverence.

“Tara, music has a purpose. You must never sing for the mere sake of it. Your voice tells a story, it brings forth rain from the sky and cures the sick. It speaks to sacred and holy beings and celebrates success on the battle field. A great man once told me, ‘You pray double when you sing’.”

I listened and learned and eventually integrated Shada’s vocal techniques with my own. She showed me how to tense and release my vocal chords, to breathe life into the melodies, to sing outside the lines and deregulate the rhythm. My voice and our songs began to take on a distinctive edge, a uniqueness not found in typical commercial music. Most of all, Shada taught me how to focus and center myself, how to connect with all of my emotions. Music flows through my veins and Shada taught me how to transmit that flow.

I recently wrote, I Praise, in collaboration with Kurt, the drummer in my band. Shada helped us assimilate indigenous chants throughout the hooks and inside the middle eight. She instructed Kurt on specific drumming techniques and taught him how to play with reverence.

Something happened between Kurt and I during the writing of that song. Something we both felt, and, something we both denied.